|

|

| Red Clay State Historical Park in Tennessee |

|

|

|

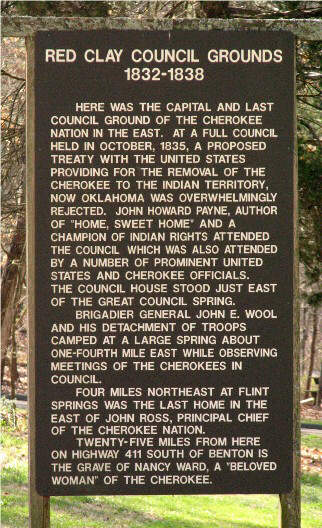

By 1832, the State of Georgia had passed laws stripping the Cherokee of our political sovereignty, banning all political activity in Georgia, and preventing Cherokees from meeting together. We were prohibited from holding council meetings in Georgia for any reason other than to cede away our land. As a result, the Cherokee capital was moved from New Echota, Georgia (see my New Echota Scrapbook Photos page) to Red Clay, Tennessee. Red Clay served as the seat of Cherokee government from 1832 until our forced removal (Trail of Tears) in 1838. At Red Clay, the Trail of Tears really began. Here we learned that we had "lost our mountains, streams, and valleys forever." (sort of **) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

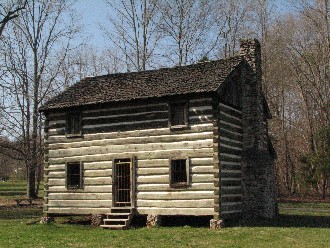

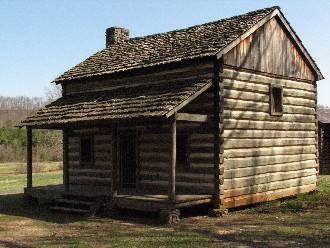

Donna and I have visited Red Clay twice. The first time was on December 30, 2004. I was transitioning from 35mm photography to digital by then. The above three shots are the only 35mm pictures I took at Red Clay. All the rest were taken with my digital cameras (Kodak in 2004). "Red Clay State Historic Area, located in southeast Tennessee on the Tennessee-Georgia border, encompasses 260 acres of forested ridges bordering a narrow valley formerly used as cotton and pasture land. The site contains a natural landmark, the great council spring or blue hole, which rises from beneath a limestone ledge to form a deep pool that flows into Mill Creek. The spring was used by the Cherokee for their water supply during council meetings." The James F. Corn Interpretive Facility which "contains exhibits on the 19th century Cherokee, the Trail of Tears, and prehistory, Cherokee art, a video theater, gift shop and a small library," was closed the first time we traveled to Red Clay, since we were there the week between Christmas and New Year's. It is the primary reason we returned on March 27, 2010. Except for these first photos of the inside of the log cabin, all of the indoor images are from our second visit. These interior shots were taken through windows. |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

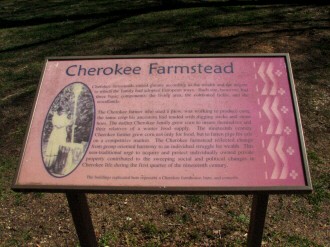

Cherokee Farmstead (sign text) Cherokee farmsteads varied greatly according to the wealth and the degree to which the family had adopted European ways. Each site, however, had three basic components: the living area, the cultivated fields, and the woodlands. The Cherokee farmer who used a plow, was working to produce corn; the same crop his ancestors had tended with digging sticks and stone hoes. The earlier Cherokee family grew corn to insure themselves and their relatives of a winter food supply. The nineteenth century Cherokee farmer grew corn not only for food, but to fatten pigs for sale on a competitive market. The Cherokee farmstead reflected change from group oriented harmony to an individual struggle for wealth. This non-traditional urge to acquire and protect individually owned private property contributed to the sweeping social and political changes in Cherokee life during the first quarter of the nineteenth century. The buildings replicated here represent a Cherokee farmhouse, barn, and corncrib. |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

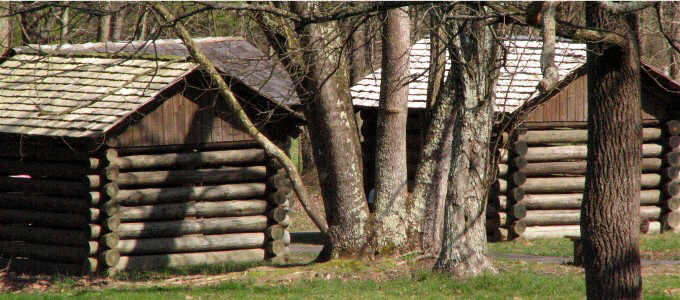

Sleeping Huts (sign text) Some of the Cherokees and their visitors at the council meetings stayed in sleeping huts similar to these three replicas. The huts had neither windows, doors, nor chinking. George W. Featherstonhaugh, an English geologist working with the United States Bureau of Topographical Engineers, made three extensive survey trips in the years 1834 to 1837. On his third expedition in 1837 he attended the October Cherokee Council here at Red Clay. “ . . . the most impressive feature, and that which imparted life to the whole, was an unceasing current of Cherokee Indians, men, women, youth and children, moving about in every direction, and in the greatest order; and all except the younger ones, preserving a grave and thoughtful demeanor imposed upon them by the singular position in which they were placed, and by the trying alternative now presented to them of delivering up their native country to their oppressors, or perishing in a vain resistance.” George W. Featherstonhaugh |

|

|

A Visitor’s Account (sign text) “Hearing that a half-breed Cherokee named Hicks had put up some huts for the accommodation of strangers, we found him out, and he assigned us a hut to ourselves, the floor of which was strewed with nice dry pine leaves. It contained also two rude bedsteads, with pine branches as a substitute for beds, and some bed clothes of a strange fashion, but which were tolerably clean. Chairs we had none; and our first care was to get a sort of table carpentered up, and to place it in such a position that we could use our bedsteads for chairs when we wrote. Our log hut had been so hastily run up that it had neither a door, nor bore evidence of an intention to add one to it, and its walls were formed of logs with interstices of at least six inches between them, so that we not only had the advantage of seeing everything that was going on out of doors, but of gratifying everybody outside who was desirous of seeing what was done within our hut, especially the Indians, who appeared extremely curious . . . A most refreshing rain fell in the evening, and about 8 p.m. somewhat fatigued with adventures of the day, I retired to our hut, from whence, through the interstices of the logs, I saw the fires of the Cherokees, who bivouacked in the woods, gleaming in every direction. Long after I had laid down, the voices of hundreds of the most pious amongst them who had assembled at the Council house to perform their evening worship, came pealing in hymns through the now quiet forest, and insensibly and gratefully lulled me to sleep.” George W. Featherstonhaugh |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

"This state historic area has been developed to preserve and commemorate the council grounds that served as the defacto capital of the Cherokee Nation from 1832 until 1837. The 260-acre park includes an interpretive center, reconstructions of the council building and a Cherokee farmstead, hiking trails, a picnic area, an overlook tower, and a 500-seat amphitheater. The focal point of the Red Clay park is the Council Spring, a large blue spring that issues more than a half-million gallons of water a day. In the early nineteenth century, the Council Spring was located in the midst of a dispersed community of Cherokee farmsteads known as Red Clay or Elawohdi, home to Charles Renatus Hicks, assistant principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. Beginning in 1816, Hicks hosted a series of national council meetings at Red Clay, establishing precedent for its later use. These general councils were often huge affairs; thousands of Cherokee citizens attended sessions and socialized at meetings that lasted days or weeks." |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

The pictures above and below are a mixture from 2004 and 2010. The top left image from 2004 shows water flowing over the bridge and stepping stones to get across that spot. By 2010 they had changed the structure, as you will see in a photo toward the end of this page. Blue Hole Spring (sign text) CHEROKEE BELIEF There is another world under this, and it is like ours in everything – animals, plants, and people – save that the seasons are different. The streams that come from the mountains are the trails by which we reach this underworld, and the springs at their heads are the doorways by which we enter it. But to do this one must fast and go to water and have one of the underground people for a guide. We know that the seasons in the underworld are different from ours, because the water in the spring is always warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer than the outer air. In the late 1880’s, ethnographer James Mooney collected legends and myths such as this from the Cherokee mythkeeper Swimmer. Mooney writes, “First and chief in the list of storytellers comes A’yunini, ‘Swimmer’ . . . his mind was a storehouse of Indian tradition.” Swimmer gave nearly three-fourths of the material in “Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees” to Mooney. Swimmer (ca. 1835-1899) was trained to be a priest, doctor, and “keeper of tradition.” He spoke only Cherokee throughout his adult life. He wore moccasins, a turban and carried his badge of authority, the rattle. |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

"Many call this sacred spring the Blue Hole, a natural landmark of the council grounds. It rises from an underground cave below the rock ledge and flows to the Conasauga and Coosa River systems. Some 504,000 gallons of water flow through here every day at a rate of 350 gallons per minute. The spring maintains an annual temperature of about 56 degrees and is approximately 14 feet deep. The spring provided water for the people at the councils and was a sacred place to them." |

|

|

|

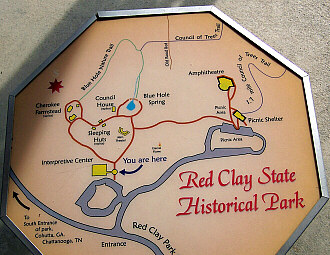

In 2004, after spending some time by the spring, we took a long walk on "The Council Of Trees Trail" before coming back to take a look at the Council House. We did not walk beyond the immediate interpretive area in 2010. Our visit was much shorter that year. All of the pictures in this section are from that 2004 visit. The map showing the layout of Red Clay State Historical Park is courtesy of the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. |

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Along the trail we came upon the Overlook Tower, although at the time we did not know what it was. We did not even know it was there, since it is not shown on the brochure map. We actually found it quite puzzling as it is very elaborate but had no signage to let you know the what, when, or why it was built. Although all of the sites I visited in preparation for creating this page mention an Overlook Tower, none of them offered any information about it either. Also, notice the couple of bent trees in the below pictures. On April 12, 2011 we were visiting the small museum at Tunnel Hill in Georgia. Through the course of conversation, in explaining what I do, I mentioned my Cherokee family heritage, at which point we were invited to come back that evening for a free presentation of "The Trail Tree Project" which was quite informative. In December of 2011, Don and Diane Wells, in an announcement for their book Mystery of the Trees, explain; "The meanings of these trees are not completely known and may never be known since most of those who know are all but gone. Some of these trees are found marking old Indian Trails. Others point to water, shelter, stream crossings, medicinal plant sites and more. The techniques for bending a tree into a particular shape, for the most part, have also been lost. However, these 'living artifacts' are a testimony to the skills and knowledge of the Indian people as they lived their lives with the idea of being one with nature." I have not checked to see if any of the trees at Red Clay are among the more than 1800 listed in the Trail Tree Database, but they are interesting. |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

"The events that made Red Clay famous happened between 1832 and 1838. Red Clay served as the seat of Cherokee government from 1832 until the forced removal of the Cherokee in 1838. It was the site of 11 general councils, national affairs attended by up to 5,000 people. Those years were filled with frustrating efforts to insure the future of the Cherokee. One of the leaders of the Cherokee, Principal Chief John Ross, led their fight to keep Cherokee's eastern lands, refusing the government's efforts to move his people to Oklahoma. Controversial treaties, however, resulted in the surrendering of land and their forced removal. Many of the Cherokee people who met at Red Clay had made remarkable advancements and lived much like the dominant culture. Many of the Cherokee had adopted the Christian religion, and their political and judicial systems were similar to that of the United States. Sequoyah (George Guess) had developed a syllabary that made it possible to write the Cherokee language. The Cherokee published the Phoenix, a bilingual paper from 1828 to 1834. In spite of the social and political advancement made by the Cherokee, Red Clay proved to be the Cherokee's last refuge – their capital in exile – before being moved westward from their homeland in the southeastern United States." |

|

|

“Friends and Fellow Citizens, We have met again in Gen. Council and greeted each other in friendship; for the enjoyment of this inestimable privilege on the present occasion, we are peculiarly indebted to the dispensations of an all wise Providence, whose omniscient power over the events of human affairs is supreme, and by whose judgments the fate of Nations is sealed.” - John Ross, opening the last Cherokee National Council meeting, Red Clay, 1837 |

|

|

|

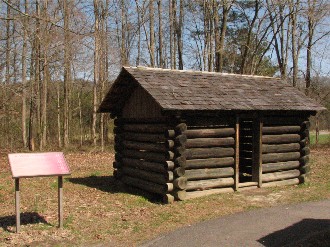

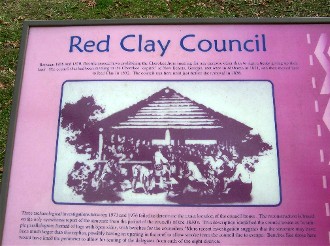

Red Clay Council (sign text) Between 1828 and 1830, Georgia passed laws prohibiting the Cherokee from meeting for any purpose other than to sign a treaty giving up their land. The council that had been meeting in the Cherokee “capitol” of New Echota, Georgia, met once in Alabama in 1831, and then moved here to Red Clay in 1832. The council met here until just before removal in 1838. Three archaeological investigations between 1973 and 1976 failed to determine the exact location of the council house. The reconstruction is based on the only eyewitness report of the structure from the period of the councils of the 1830’s. This description identified the council house as “a simple parallelogram formed of logs with open sides, with benches for the councilors.” More recent investigation suggests that the structure may have been much larger than this replica, possibly having an opening in the roof to allow smoke from the council fire to escape. Benches like those here would have lined the perimeter to allow for seating of the delegates from each of the eight districts. |

|

|

|

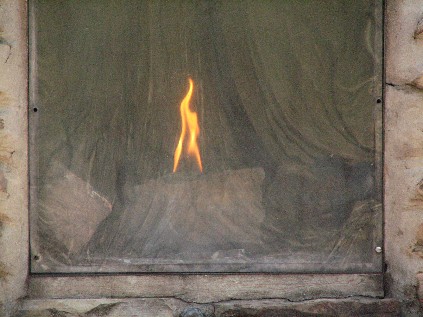

Sometimes called the Fire People, an important part of Cherokee life was the Sacred Fire traditionally kept burning in the Council House. In 1984 the Eastern and Western Cherokee Nations came together at Red Clay. As part of the commemorations they established the Eternal Flame of the Cherokee Nation memorial. In 2004 when we came off from The Council Of Trees Trail, we were approaching the memorial from behind. Without even knowing what it was yet, I took the below picture looking across the grounds (an almost identical version of it opened this page because I liked the shot enough to take a digital and 35mm photo). In 2010, I was approaching it from the opposite direction for the image second row down on the left. I have included this image because I like the symbolism of placing the tree behind the Eternal Flame with the many branches heading out in a variety of directions, just like us, the Cherokee. |

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

"The Cherokees carried hot coals from their council fire at Red Clay on the removal to Oklahoma. In the 1950's the flame was transported to Cherokee, NC, and then in April 1984 ten Cherokee runners with torches returned the fire to Red Clay, demonstrating that the Cherokee spirit is unquenchable." |

|

The James F. Corn Interpretive Facility obviously got a paint job between 2004 (above left) and 2010 (above right). As already mentioned, it was closed in 2004 because we came between Christmas and New Year's. All of the inside pictures are from 2010. Since this page is already fairly photo heavy, I am going to make that a separate page. You may click on either of the above pictures to go there now or wait until the bottom of this page where it is also linked. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The thing I needed to keep in mind on our second visit here, when there were more people around, is that in addition to being an historical site for the Cherokee, Red Clay is simply a local park for many of those who come here. The above picture is not, of course, the 500-seat amphitheater. This is shown on one map as the Mini-Theater. We did pass through the large amphitheater coming off from The Council Of Trees Trail in 2004. I did not take any pictures of it, but I remember we paused and sat for a moment, because I recall striking up a conversation there with one of the few other people in the park that day. She was a Christian woman who could not understand how I could honor my Cherokee family heritage, particularly maintaining a number of traditional perspectives, and yet still be a Christian. We had a pleasant enough conversation, and I gave her a card with my website address, but it was a good reminder for me that a number of people still perceive anything Indian as being incompatible with Christianity. This section finishes the page with several miscellaneous images, including a special occasion photo shoot going on by the spring (here is where you can see the remodeled bridge), pictures of some park visitors who got my attention because they brought along their goats, and an old goat (the one wearing the Cherokee ball cap) with his wife. |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

** Some Final Thoughts ** Why is there a (sort of **) at the end of the opening paragraph on this page? Well, because even though our presence has been significantly diminished, we did not lose all our mountains, streams, and valleys forever. While things changed considerably, we did not disappear. Even many of our values from before European contact have survived in spite of immense pressure and tragedies. Our language has survived. It is taught in our schools, and even beyond them though the Internet and other modern tools. Our cultural heritage and history have survived. Thousands are reached with our story through our organizations and individuals everyday. We have survived, and flourish. Though legally we are three federally recognized tribes, and countless others, we are one people in heart. As best as I can tell from the statements of my family elders, I am about seven generations from any full-blood Cherokee connection. If you wish to play percentage games, it is the smallest piece in my personal American puzzle. Yet, for me, when it came looking for me, the Cherokee spirit grabbed hold of me with a passion, and has become the single biggest expression of any of my family heritage histories. When even those of us with such a distant tangible connection, discover we are bound by the heart to the story of those who walked before us, and feel compelled to share it, so those who shall come after us will understand, and hopefully connect, nothing can be lost forever. Wado Unelanvhi. |

|

Quoted text

and information courtesy of: |