|

|

The Cherokee Story of

Indian Pipe (a lesson in humility and peace) |

|

|

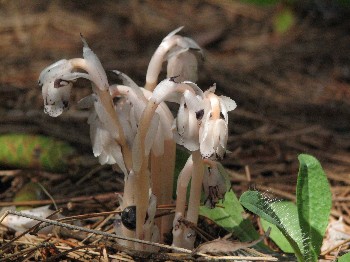

The Great Smoky Mountains Before selfishness came into the world, which was a long time ago, the Cherokee happily shared the same hunting and fishing lands with their neighbors. However, everything changed when selfishness arrived. The men began to quarrel with their neighbors. The Cherokee began fighting with a tribe from the east and would not share the hunting area. The chiefs of the two tribes met in council to settle the quarrel. They smoked the tobacco pipe but continued to argue for seven days and seven nights. The Great Spirit watched the people and was displeased by their behavior. They should have smoked the pipe after they made peace. The pipe is sacred and must be treated with respect. He looked down upon the old chiefs, with their heads bowed, and decided to send reminders to the people. The Great Spirit transformed the chiefs into white-gray flowers that we now call “Indian Pipe.” The plant grows only four to ten inches tall and the small flowers droop towards the ground, like bowed heads. Indian Pipe grows wherever friends and relatives have quarreled. Next the Great Spirit placed a ring of smoke over the mountains. The smoke rests on the mountains to this day and will last until the people of the world learn to live together in peace. That is how the Great Smoky Mountains came to be. — Lloyd Arneach (Eastern Band of Cherokee)

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

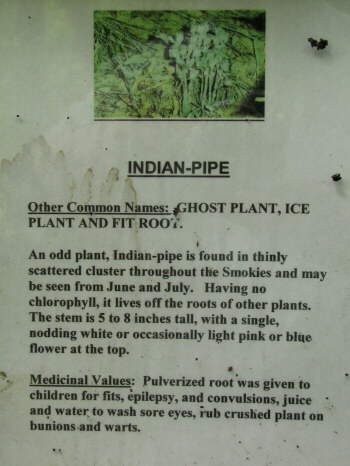

The pictures immediately following the legend are mirror versions of the same photo. The sign in the middle and the above left information image were taken at the Junaluska Medicine Trail, which is part of the Junaluska Grave, Memorial & Museum grounds in Robbinsville, North Carolina. There are no Indian Pipe plants in the photo of the sign. It was too early in the season. I just liked the sign. I actually became fascinated with Indian Pipe long before I ran across the Cherokee legend, or visited the Junaluska site. I first noticed it in September 1997 on Donna's mom's property in the Boyne Falls area of northern Michigan. Over the years, I have taken more than two hundred pictures of it anywhere from early August to mid-September, which places it a little later than it apparently shows up in the Smokies. According to a USDA map from the Internet, Indian Pipe has quite a broad range in which it grows.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Indian Pipe plants up north (on Donna's mom's property), at least those which I have taken photographs of, tend to grow beneath groups of pine trees, so it can be quite a challenge to get a good (focused) shot. But, the light can be fascinating as it filters down through the pines providing opportunities. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

University of Arkansas • Division

of Agriculture Plant of the Week Indian Pipe Latin: Monotropa uniflora The dainty, extremely delicate flowers of the epiparasitic Indian pipe appear in the fall following a rain. We all know how plants are supposed to behave but, apparently, some never got the memo. Variation in environmental requirements and form are commonplace but some even go so far as to change their way of obtaining food. Indian pipe (Monotropa uniflora), for example, has foregone photosynthesis and lives by thievery. Indian pipe is an herbaceous woodland wildflower of the eastern deciduous forest of the United States and Canada with a tremendous range of distribution. In addition to our neck of the woods, it is also found in high, cool mountains of Central America and northern parts of South America, Japan, China, the Himalayas of southern Asia and India. It has a wider range of distribution than almost any modern plant, indicating it probably evolved during the Jurassic period during the peak of the dinosaur era before the supercontinent of Laurasia separated. It belongs to its own family, the Monotropaceae, but is closely allied with the azalea family and some authorities place it there. Indian pipe grows 6-to 8-inches tall. It is an unbranched plant with a solitary nodding flower that pushes through the soil with its crooked flower already formed. Usually several stems arise from an underground crown. The stem, the scale-like leaves and the flower itself are waxy, extremely fragile and white or sparingly infused with pink. Because of its lack of chlorophyll, it is sometimes called ghost plant or corpse plant. The single five-petal flower is up to about an inch long. When the bloom is pollinated, it rotates upward and the seed capsule matures in an upright position. The stems turn black as they die. Flowers appear in late summer and fall following a soaking rain. Indian pipe derives its carbon stores, not from photosynthesis, but by stealing them from a mycorrhizal fungus living in the root zone of the forest. Mycorrhizal fungi are beneficial (symbiotic) organisms that vastly expand the absorptive surface area of a tree’s root system and aid in uptake of specific nutrients such as phosphorus. In exchange for scavenging for nutrients the tree reciprocates by providing carbohydrates for the fungus. Germinating seedlings of Indian pipe chemically mimic the tree’s root system causing the mycorrhizal fungi to attach to the roots of the imposter in a kind of biological identity theft. The tree sends its sugars produced in photosynthesis to the fungus mycelium which in tern passes some along to the thieving Indian pipe. This arrangement is called epiparasitism. Indian pipe is only able to feed on one group of mycorrhizal fungi, the Russula. These beneficial fungi are able to attach to a wide variety of tree species including oaks and beech. Cool, moist and shaded conditions favoring the accumulation of thick deposits of leaf litter favor the development of the mycorrhizal fungus and mark the kind of location where Indian pipe is likely to grow. Though an interesting and relatively rare native Arkansas wildflower, Indian pipe will never be grown in the garden. Its specific requirements and epiparasitic ways make it all but impossible to cultivate. By: Gerald Klingaman, retired courtesy of http://www.arhomeandgarden.org/plantoftheweek/articles/indian_pipe_01-12-07.htm |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

The picture above on the right reminded me of a horse's head. That is the reason it got included. I will have used about 70 or 75 of the roughly 250 images I had to choose from when I finish this page. It can be a daunting task to narrow things down. Sorry if this was a little more than you cared to see of one plant. But, like I said, it has fascinated me from long before I read of the Cherokee legend. The poet in me, of course, likes the legend more than all the scientific stuff. Still, the thought of it having been around since the days of dinosaurs was interesting. Plus, the "We all know how plants are supposed to behave but, apparently, some never got the memo" text endeared it to me even further. Since I tend to function outside of the boxes as well, it sort of feels like a kindred spirit. I also ran across a book cover while I was doing an Internet search about it. While it is not a photo of mine, I decided to include the graphic anyway. I just liked it. I thought it added to the page. And, fittingly, it is a book of poetry. |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|