|

|

| Cherokee Heritage Center - Cherokee National Museum |

|

|

| Cherokee Heritage Center - Cherokee National Museum |

|

|

|

I originally started this page with the same photo (inside the museum) as the link photo on the opening Tahlequah page. But, I decided instead on this image I shot in 2001. Usually I take numerous photographs of trees, flowers, bushes, and other natural items wherever I travel. Yet, surprisingly, I think this is the only picture of this sort I took at the CHC. We were approaching the entrance to the museum when I noticed this branch. It seems to me to embody the spirit of this place, as well as the Cherokee people in general . . . at the same time, both full of vibrant new life and yet also the potential for pain. I did not check to see how solid, or sharp, those thorns were. But I know the sharp pain of betrayals, removal, and subsequent treatments by white Americans remains. Healing begins with truth and the realization that this is about Americans. Each of us. |

|

|

|

|

Outside the entrance to the museum you will find a number of busts of some of the key players in Cherokee history. You will also see the remains of the columns from the First Female Seminary (displayed on the seminaries page too) which was originally located on this piece of land. |

|

The museum building was designed by Cherokee architect Charles Chief Boyd. Built low to the ground and illuminated at both ends by natural lighting, it is meant to symbolize a traditional Cherokee dwelling. As we enter the building, before I forget, if you were to visit the Cherokee National Museum, you need to know that photography is not allowed in the exhibits area. I called the museum in advance, explained why and how I intended to use these images, and received special permission to take the pictures you will see on this page. |

|

|

According to the brochures, "the museum serves five main functions; it houses the permanent Trail of Tears exhibit, temporary exhibits, two major art shows each year, and the genealogy center. Administrative offices are located in the basement. An uniquely designed structure of concrete, steel and native stone from the area, the Cherokee National Museum is constructed on the National Register of Historic Sites location of the old Cherokee Female Seminary which operated on the site from 1851 to 1887 until it burned. Three brick columns remaining from the old structure are surrounded by a reflecting pool which continues into the beautiful lobby of the Museum. Reminiscent in design of an ancient Indian structure, the climate-controlled building is contemporary in every respect. Surrounding the old columns are the initial memorials of the Cherokee National Hall of Fame, saluting famous Cherokees who have made significant contributions to the American Nation as a whole. Paying tribute with remnants of history to the ancient Cherokees as well as to the modern, exhibits in the Museum include ancient artifacts from archeological 'digs' in the ancient homelands of the Cherokees as well as exhibits relating to the Cherokee history of the present. Special exhibits are arranged in the Keeler Gallery on a rotating basis. The Museum also houses an outstanding collection of Indian artists' interpretations of the 'Trail of Tears.' Temporarily housed in the Museum is the beginning of what will become the largest collection of books, documents, reports and correspondence in the world relating to Cherokees and their history." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

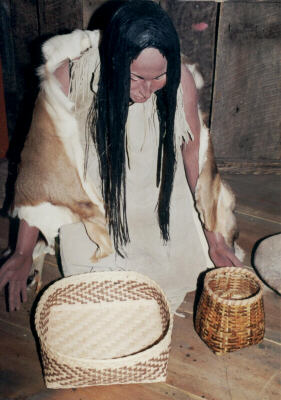

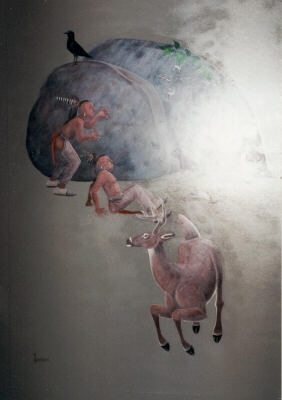

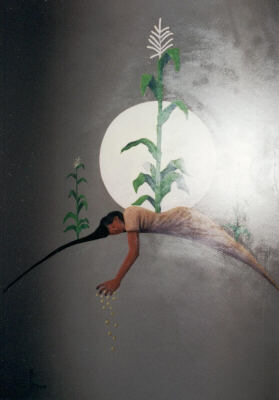

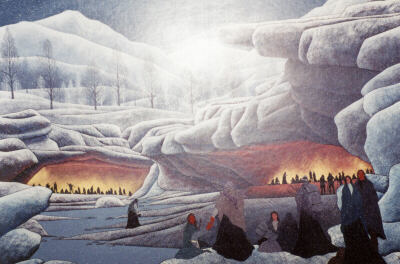

In 2001 the museum had not yet completed the new Trail of Tears exhibit. The displays were a little different than when I returned in 2004. A few Cherokee legends were highlighted like the "two bad boys who found where the hunter (Kana'ti) hunted for game. The foolish boys, thinking they too could hunt, opened the cave by sliding back the large stone, and all the animals rushed out. Because of the two bad boys, animals are no longer so easily hunted." Or, "Selu (the corn mother) who provided food for her family by rubbing her belly. When she did this, bright kernels of corn fell from her body." Some artwork remains, and some has changed. The woodcarving above is 'Exodus' by Willard Stone. I do not have notes on the paintings, but I assume the CHC could answer any questions you might have about them. As you can tell, 2001 was before digital photography for me. One of the advantages with my digital camera, over my 35mm the above photos were taken with, is I would know right away that the flash washed out part of several of the images, and could reposition, or try shooting without a flash. |

|

|

|

|

It is interesting, as I look at my 2004 pictures from the museum, that they are all about the Trail of Tears exhibit. At this particular moment, I do not even recall the other displays. I do know, as usual, by the time I finished outside in the villages, and got inside to the museum, I was running pretty late. And I specifically wanted to visit, and experience, (as well as photograph) the area where you walk the trail among sculptures of individuals, which they were working on in 2001, but had not finished. The exhibit welcomes you with this simple image and message, "In 1838, 16,000 Cherokee were driven from their homes and forced to move west into Indian Territory. This tragic exodus became known as the Trail of Tears." I sometimes wonder if I focus entirely too much on the Trail Where They Cried, instead of the many great accomplishments both before and after. But, it is compelling, and in the remembering, perhaps we can all learn and grow. |

|

|

|

If you have visited some of my other Scrapbook Photos pages, you might recognize the Chief Vann house, and the tavern from New Echota in the display below (left) highlighting some things about the times before the Trail. Titled "Playing By the Rules," the text on the various signs reads: 3A “By the early 1800s, most Cherokee had adopted at least some white ways. They established businesses, farms, Christian churches, and a government similar to that of the United States. At the same time, the Cherokee had succeeded in maintaining their culture, preserving many traditional ways. Even newly drafted laws upheld such tribal traditions as land held in common and matrilineal power." 3B "In the Old Nation, the Cherokee used stories to explain traditional values to their children." 3C "This house in Georgia was built in 1805 by Cherokee James Vann. It was part of a large plantation that included slave quarters, orchards, and about 800 acres of farmland. The home is now a Georgia State historic Site." 3D (Next to a Cherokee Hymn Book) "Many Cherokee embraced Christianity. After the Bible was translated, Elias Boudinot and Reverend Samuel Worcester worked together to translate Christian hymns into the Cherokee language." 3E "In 1827, the Cherokee established a constitution, modeled after that of the United States. Soon, written laws formalized Cherokee legal traditions. Many such ideas were far ahead of their time, such as the law providing that a woman could transfer her separate property without her husband’s consent." 3F "Many Cherokee began to attend missionary schools. This education allowed them to better compete with white society. Future Cherokee leaders gained oratory and debate skills that would prove critical in the turbulent years ahead." 3G "Vann’s Tavern (now relocated to New Echota State Historic Site in Georgia) was typical of the kinds of businesses many Cherokee operated." I like the imagery (below right) of the young and the old sitting around the fire, storytelling, while the shadow of the mythical Phoenix (i.e. rising up from the ashes) protectively engulfs them. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From my Cherokee History Timeline and the New Echota pages, you should be familiar with each of these gentlemen who appear on the walls of the museum. John Ross (left) was the elected Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation at the time of the Trail of Tears. John Ridge (center left) and Major Ridge (center right), along with Elias Boudinot (not pictured here, but his bust opens this page) were leaders in the opposing political party who entered into the fraudulent New Echota Treaty. And, of course, President Andrew Jackson, whom the Cherokee had assisted during the war of 1812, which helped him rise to national status, and ultimately the Presidency of the United States. His way of saying thank you was the Indian Removal Act, refusing to protect Cherokee sovereignty even after the United States Supreme Court ruled in favor of that status, and, of course, the underhanded dealings in bringing about the Treaty of New Echota. I will not reiterate the details here since they can already be found in both the timeline (access through the Cherokee Bill's Teaching Center primary page) and the Scrapbook Photos tour of New Echota. |

|

I do not remember what this display (pictured at right) was about, although it may have simply been an example of a pre-removal Cherokee home. I included it because I like the picture. Not everybody afforded the luxury of the Cherokee Chief James Vann home (3C above) which was built 34 years before removal (see also its separate Scrapbook Photos page). But, the average Cherokee was a far cry from the "savage Indian" our history books tell us were removed to make way for "civilized" white Americans. |

|

|

When you hear the large numbers of deaths associated with the Trail Where They Cried, people often assume it was the march which took all these lives. But, the truth is, many of those lives were lost even before the trek west began. Models and sketches have too clean a look to truly allow one to appreciate the appalling conditions Cherokees were herded, and crowded, into. |

|

|

|

|

“Collection

Forts” "Captured Cherokee were first crowded into temporary holding forts or stockades for one or more weeks. Bad sanitary conditions, lack of privacy, nonexistent washing and bathing facilities, foul drinking water, and unhealthy food demoralized the Cherokee. Worse, they created serious health hazards. Sickness was widespread. Many Cherokee died during the roundup and while in captivity." |

|

The text on one of the signs I photographed told of these events, “An eyewitness said that the soldiers, whooping as they went, sometimes herded the Cherokee like cattle, driving them through rivers without a chance to take off their shoes. — A Cherokee who was deaf and mute was shot to death for turning right when a soldier said to go left. — When a man struck a soldier for goading his wife with a bayonet, he received 100 lashes as punishment.” |

|

|

— |

|

|

"Many walked. Some traveled by wagon, steamboat, or barge. Some marched in chains. Thousands marked the way west with their graves. Their passage would leave a permanent scar on American history." (19A) |

|

|

|

|

Exhibits 19 and 20 were titled "Many Trails" and "Many Tribes." If you have ever heard someone refer to the "Five Civilized Tribes" this is what they were referring to. Besides the Cherokee, the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole all endured their "Trail of Tears." The text I will share with you here is a combination for each tribe from the two separate displays. 19C and 20A speak about the Choctaw Nation which "reluctantly agreed to removal in 1830. More than 16,000 left Alabama and Mississippi to travel along the 350 mile 'Trail of Tears' to Indian territory over the next few years. Traveling by foot, horseback, wagon, and steamboat, they struggled through blizzards, floods, lack of supplies, and cholera. Approximately 25 percent of the Choctaw perished during the removal period between 1831 and 1833." "By the time Indian territory became the state of Oklahoma in 1907, the U.S. government had abolished tribal ownership of land and the Choctaw tribal government. The Choctaw Nation, however, survived and operates today under a constitution adopted in 1983. It has become one of the primary players in the economic development of southeastern Oklahoma. Some Choctaw passed through Louisiana during their forced removal to Indian Territory. Alfred Boisseau, a French artist, captured some of them on canvas" (20A upper left painting). 19D and 20B tell us about the Chickasaw Nation, whose last treaty "allowed them to arrange their own emigration. Optimistically, they began their trek in 1837, along the northern route of the Choctaw. The Chickasaw arranged, at great expense, to have pork and other food waiting along the trail. Hundreds of barrels left by unscrupulous contractors to rot in the summer heat were worthless by the time they got to them. Then, emigrants found themselves in the lock of winter far from their destination when smallpox struck. Only 6,000 survived the journey." "The removal of the Chickasaw from their southeast homelands began in the early 1800s. Government traders who forced tribal members into debt demanded payments. By 1818, the Chickasaw had unwillingly yielded property in Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Despite broken treaties and forced removals, the Chickasaw people survived and remained united. Today, they prosper in south-central Oklahoma as a culturally progressive and financially successful nation. The (upper right) painting, by Tom Phillips, depicts a burial during the Chickasaw removal." 19E and 20C inform us about the Muscogee (Creek) who also "reluctantly signed treaties (in 1825 and 1832) which exchanged the last of their cherished ancestral homelands for lands in Indian Territory. In 1836 and 1837, during their terrible journey on the 'Trail of Tears,' half of the 20,000 tribal members forcibly removed by the U.S. Army perished." "The Muscogee (Creek) people, as well as the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole, are descendants of a remarkable culture that, before A.D. 1500, spanned the entire region now known as the southeastern United States. The Muscogee were not one tribe, but rather a union of several that evolved into one of the most sophisticated political organizations north of Mexico. Following removal, the Muscogee quickly began rebuilding their government – only to find it abolished by the federal government in the early 1900s. In the 1970s, the tribe drafted and adopted a new constitution and restored its national council. Muscogee removal is depicted by artist Sandra Peters (lower left painting)." 19F and 20D are about the Seminole Nation. 19F was too blurry for me to make out much of the text, but what I could read tells us the Seminole Nation did not enter into a removal treaty with the U.S. government. Their removal from ancestral homelands was as prisoners of war. Captured Seminoles were shipped in shackles and chains to Indian Territory. "The Seminole people originated in Florida and consist of many tribes indigenous to the southeast. Encroachment by white settlers and slave-hunters into tribal territory sparked the Seminole Wars in 1817. The Seminole fought three wars against the U.S. government. For the U.S., these were the most expensive wars fought against any tribe. Hulbutta Micco (Billy Bowlegs) was the last war chief to leave Florida in 1858. The government’s war against the Seminole ultimately failed. Today, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Seminole and Miccosukee tribes in Florida successfully continue their lives and traditions. (artwork) Seminole Warriors awaiting “Miccosukee Victory,” also known as Dade’s Massacre. |

|

|

|

At #22 we are back to the Cherokee, and see that theirs (like others) was not a single trail, but several. Once again, I will not go into great detail here because the information is already in the timeline and New Echota pages. Basically, after the U.S. Congress ratified the fraudulent Treaty of New Echota, President Jackson gave us two years for voluntary removal before he would send in federal troops. When only about one thousand Cherokees had moved at the end of the two years, the troops were dispatched. Those forcibly removed and first sent in the spring of 1838 had so many deaths that the bulk of the people were kept detained in the stockades until fall, which turned out just as tragically. This display shows the different routes taken by the various detachments. Cherokee leaders, by their request, were given permission to organize and oversee the fall departures. They divided into thirteen groups of 1,000 or more. Imagine the incredible task of moving so many thousands of people, so far, before the benefit of modern transportation. "September, 1838 – Preparations for departure continued. Roughly 1,000 travelers made up each detachment. Two Cherokee leaders were in charge of each group, and members of the Cherokee Light Horse Police served to maintain order. Chief John Ross negotiated for $65.88 per person to cover the costs of removal. Such expenses would include wagons, horse and ox teams, food, clothing, ferry and turnpike fees, conductors, wagon masters – and gravediggers." |

|

|

|

"As a result of their roundup, captivity, journey, and re-settlement, many Cherokee died. No one knows the exact number of deaths caused by removal, but estimates range from 2,000 to 4,000." |

|

|

"This pattern (on the wall) is based upon a contemporary bead pattern called the ‘Trail of Tears,’ by Cherokee artist, Mary Foreman. The 16,000 beads represent the number of Cherokee in the ‘Old Nation’ at the time of removal. The 2,000 rough, black beads used for the lower footprints represent conservative estimates of the dead. The 2,000 textured, red beads used for the upper footprints represent additional deaths estimated by Elijah Butler, physician for the first detachment. The 12,000 smooth, white beads represent the Cherokee who survived." |

|

Here is where you join the trail yourself. While I will share some of the photos I took in the midst of them, it cannot begin to convey how it feels to stand among them. If you ever have the chance to experience this for yourself, you should not pass up the opportunity. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

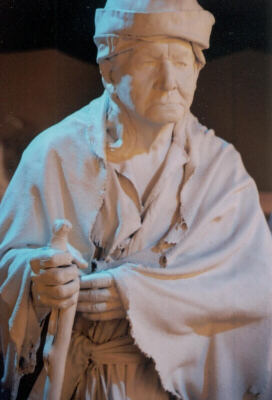

I have intentionally placed the photo of this elder alone in this spot. I already mentioned that by the time I got inside to the museum, I was running substantially late. So, I was shooting pretty quickly, trying to take as many pictures as I could before closing time, gleaning what little information I might manage along the way. When you enter this area you come in from behind. I do not remember if it was as I rounded this figure and looked into his face, or if the feeling had begun earlier, sort of looking ahead over my shoulder, as I was shooting back, yet sensing something unusual. I do not know if it was deja vu, or some sense of knowing this person, or something else entirely. All I can tell you is, it was one of those other-worldly moments in life that makes your hair and skin tingle and your spirit stir. No matter where I put my tripod, for whatever shot I was taking, I kept looking over at him, as if I were waiting for him to speak to me, or do something. So, whoever he was, or is, I give him this special place now. |

|

click on photo for better picture |

|

As we wrap up our visit of the museum, I share the below five photos. The top three I have no notes about, although the middle one is obviously a printing press, and something about the Cherokee Phoenix (see more about it in the New Echota pages). The last picture (36A) is interesting. I took several shots of this. Initially my thoughts were to find an angle to reduce the reflection it was picking up from another display. But, the more I thought about the artwork and text, the more I concluded that the reflection of the home actually added to the symbolism of the image. I have not included the Cherokee Syllabary, since most of you do not have the Cherokee font in your computer and it would be converted to something making no sense (the Cherokee I have shared with you I converted to graphics rather than just typed), but the 36A text follows. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sacred Fire “There is just a simple instruction that also comes from the Creator, and He said, [Cherokee Syllabary omitted] That means, ‘build one fire.’ [Cherokee Syllabary omitted] ‘Stay close to that fire.’ I would say that fire that we talk about has to be the Cherokee Nation. That has to be our central fire and we’re instructed (by the Creator) . . . . [Cherokee Syllabary omitted] ‘Be close to that fire. Be near to that fire.’” – Benny Smith, speaking at Chief Chad Smith’s inaugural address, 1999. As we were leaving the Heritage Center grounds (in 2001), I stopped to take one final picture. |

|

|

|

Text shown in quotation marks throughout these pages comes from various brochures, pamphlets, information sheets, other items picked up or photographed on our visits, Cherokee Heritage Center assistance, and Internet searches. See the links pages. |

|

|